Ethics in Healthcare Webinar: Highlights

Highlights of Ethics in Healthcare Webinar

What’s morally right and wrong differs from person to person, according to an intriguing recent AMN Healthcare webinar, “Ethics in Healthcare.”

“Your bioethics is a set of moral principles,” said presenter Cathy Massaro, MSW, CCM, ACM-SW, AMN Healthcare Revenue Cycle Solutions clinical workforce manager. “It's the beliefs and values that guide us in making choices.”

People face ethics questions every day, at home and on the job. Ethics guide people’s actions and are extremely important. Ethics enhance quality of care, foster professionalism, promote the organization’s culture, and improve staff morale and performance.

“We need to know the ethical issues that are out there and to understand the ethical implications of the care choices,” Massaro said.

What is bioethics?

Bioethics refer to the beliefs and values to make medical care decisions. Bioethics includes research, health policy, genetics, precision medicine, reproduction, shared decision-making, social determinants of health, and neurological and brain function.

Several influences affect medicine and patient care. These include advances in medical science, better-informed patients, litigation, awareness of treatment costs and conflicting obligations.

“These are all conflicts that impact the decisions patients have to make with your assistance and guidance,” Massaro said.

The four principles of ethics in healthcare

The four principles of medical ethics are autonomy, beneficence, nonmaleficence and justice.

Autonomy honors patients’ right to make their own decisions, but it’s not that simple, Massaro explained. Other people can influence patients’ choices. And it depends on the patient’s competence to make informed decisions and the capacity or ability to think and act on their own.

Beneficence helps the patient advance what is in his or her best interest, not what is best for the clinician, the hospital or research. It also refers to accepting the patient’s choice to end care if that is in his or her best interest, Massaro said.

Nonmaleficence refers to doing no harm. It includes explaining the risks and the side effects of a treatment; labeling someone, especially when it comes to psychiatric conditions; and weighing the benefits as compared to harms.

Justice means to be fair, including the distribution of resources; treating like cases alike; addressing competing needs; upholding the patients’ rights; and avoiding any potential conflicts with legislation, she said. The burdens and benefits must be distrusted equally, Massaro reported.

In addition, Confidentiality may be considered a fifth principle, but it is not absolute and may be breeched if in the interest of public health.

Handling ethical dilemmas in medicine

“When working through an ethical situation, there is a course of action and a pattern to it, a reasoning,” said Massaro, adding, “You may not realize you are dealing with an ethical situation, but you are. They are all around us. They’re so important because they help us meet the patients’ expectations.”

The patient’s morals will come into play. Morals refer to the person’s traditions, customs, laws and beliefs that are called on for guidance in determining what action to take. Communities often have common morals, she added.

Ethical conflicts happen when there is a question or conflict associated with competing ethical principles, personal morals, standards of practice or when someone considers violating the principles, morals and standards. What is the right decision? Who can make the decision? What happens when goals and values differ? The resulting stress affects patient, family and professional caregivers.

The process to address ethical issues include clarifying the conflict, recognizing the stakeholders and their values, understanding the circumstances and identifying the ethical perspective relevant to the issue. Then note the different options, select one, share and implement that decision, and review the decision to make sure it achieved the desired goal, she explained.

“Communicate the decision; communication is critical,” Massaro said.

Refusing care presents clinicians with ethical conflicts. The reasons patients refuse treatments that will prolong life include religious reasons, expense, risk and quality of life. Healthcare workers must respect that choice.

“Every competent adult has the right to refuse unwanted medical treatment,” Massaro said. And that right holds even if the refusal could result in death.

Withdrawing and withholding treatment may include ventilators, feeding tubes, cardiopulmonary resuscitation and dialysis. Patients may think the burdens outweigh the benefits, or that the treatment is dehumanizing or uncomfortable.

“Just because we can does not mean we should,” Massaro said.

Competence and capacity are critical and can become murky, unless the court has decided the person is not competent. Physicians determine if the patient has capacity and is able to make healthcare decisions.

Pediatric decision-making presents challenges, because parents may refuse treatment for themselves but not their children. The best-interest standard applies in pediatric care.

Physician-assisted death is another ethical issue. Each state determines if physicians are allowed to hasten a competent terminally ill person’s life. Eleven states allow the practice, which can maximize comfort, respect patient values, address their fears and optimize a patient’s quality of life.

End of life care may present ethical challenges, because patient goals and preferences vary among patients. Some may want more aggressive treatment and others opt for comfort care or physician-assisted death.

“There is no right or wrong; it is what is best for the patient within the laws of where they are at,” Massaro said.

Patients should complete advance directives and select a healthcare surrogate to make decisions if incapacitated.

Informed consent must be obtained before care is given, it should include a full description of what treatment is planned and the patient needs to be competent to make that decision. It can, however, be expressed or implied, especially if there is a literacy issue.

The patient “needs to know what they are saying ‘yes’ to,” Massaro said. If you are not the person to have the conversation, you must advocate for the right person to spend that time with the patient.”

Other issues include fairly distributing limited healthcare resources and supporting social programs.

Professional caregivers must respect the patients and their decisions and values, act in the patient’s best interest and adhere to the organization’s mission, values and vision. The aim must be to do good, do no harm and be fair.

“Ethics and quality of care go together,” Massaro says. “You want to avoid any issue that causes harm.”

For more information

For access to the full webinar, “Ethics in Healthcare,” join us on our AMN Healthcare YouTube Channel!

The AMN Healthcare Revenue Cycle Solutions monthly webinar series offers exciting and informative programs to help people’s careers and professional lives. Upcoming events will cover a variety of topics including coding updates, data leadership monitors and clinical documentation integrity.

Additional Revenue Cycle Resources:

- Cancer Registry: Learn about Cancer Registry careers and opportunities.

- Case Management Utilization Review: Join a team pairing decades of Revenue Cycle knowledge with the support of one of healthcare’s most trusted brands.

- Refer-a-Friend: Make up to $2,000 per referral.

Latest News

Case Study: Establishing a Strong Financial Foundation through a Commitment to Quality

Our recent cases study showcases how a healthcare organization in the South tackled issues with its quality scores and revenue by implementing a Clinical Documentation Integrity (CDI) program in

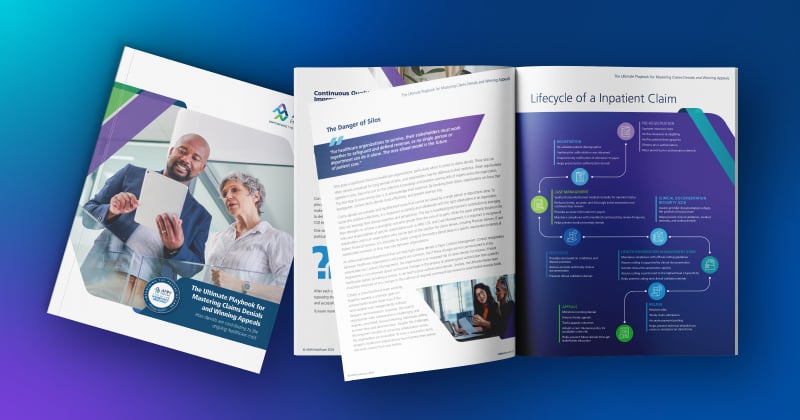

The Ultimate Playbook for Mastering Claims Denials and Winning Appeals

This comprehensive guide examines the complexities of appeals and denials and offers critical strategies for navigating toward a more financially stable future for healthcare organizations

Continuous Quality Improvement: Using the PDSA Cycle to Solve Claims Denials

One effective Continuous Quality Improvement (CQI) model is the PDSA (Plan-Do-Study-Act).

Webinar: Protecting Your Healthcare Data: Uncovering Vendor Cyber Security Threats

In this recorded webinar, you will discover how to safeguard your data, the top qualities to look for when selecting a secure vendor, and cyber security best practices to protect your valuable

Case Study: Advent Health Reduces Avoidable Days to Improve Patient Satisfaction & Drive Savings

Download the full case study to discover how AdventHealth partnered with AMN Healthcare Revenue Cycle Solutions (RCS).

3 Strategies for Cultivating a Culture of Connection, Development, and Loyalty in the Modern Workplace

Explore job satisfaction: Learn 3 strategies for fostering connection, development, and loyalty in our white paper.

Outpatient Clinical Documentation Integrity Solution

The current trajectory of U.S. healthcare points to the growing number of outpatient visits and procedures. As a result, alignment of quality measures, data accuracy, and revenue integrity are

The Five Pillars of Trauma Revenue

AMN Healthcare's Trauma Billing Program provides a method for recovering the cost associated with the Trauma Service and a pathway to a stronger financial future.